Monopoly, the commercial dividend of powerful brands

My favourite episode of South Park is ‘Gnomes’. Not only is it properly funny, if you like your humour puerile and immature, but it also holds a small cautionary tale for marketers.

‘Gnomes’ tells the story of a gang of animated garden ornaments that live beneath South Park and steal underpants while its residents are asleep. When pressed on their reason for nicking all the knickers, the Gnomes reply that it’s all part of a carefully constructed three-phase plan.

The Gnomes explain that phase one is to collect underpants. And phase three is that they make a profit. But they are remarkably sketchy about stage two, the means by which depriving Southpark of its grundies actually results in any profit whatsoever. Indeed, in a short presentation the gnomes have knocked up, stage two is merely represented by a whopping great question mark.

And doesn’t that sound like our industry all over? Not the underpants thing obviously but the absence of any real understanding of phase two.

Phase one is that we build brands, of that we are certain. And phase three is our, all too often blind, assertion that our clients or businesses will make a profit. But time after time the middle bit is genuinely marked by a collective crossing of fingers.

Small wonder that so many people, client and agency side cling onto best practice, accepted wisdom and observed rules, for dear life. Since, without an understanding about how what we do actually works, precedent is all we have to fall back on.

Of course, we are all well versed in the results of creating strong brands, this much is passed from generation to generation of marketers. They build and defend market share. They create barriers to entry for competitors. They lower price elasticity and create platform for charging a premium. They create a store of trust that helps insulate the business from reputational damage. They create organisational discipline that fosters internal confidence and innovation. And so on.

But how? How do they do this? That’s always seemed to me to be the phase two that is missing from our collective understanding of what we are actually up to.

A very long time ago a rather wise planner told me something I had never heard before and to be quite honest have never heard since, so it is either absolute genius of rank charlatanism. It’s an explanation for the reason that brands create value that is breathtakingly simple and might represent a phase two that actually makes sense.

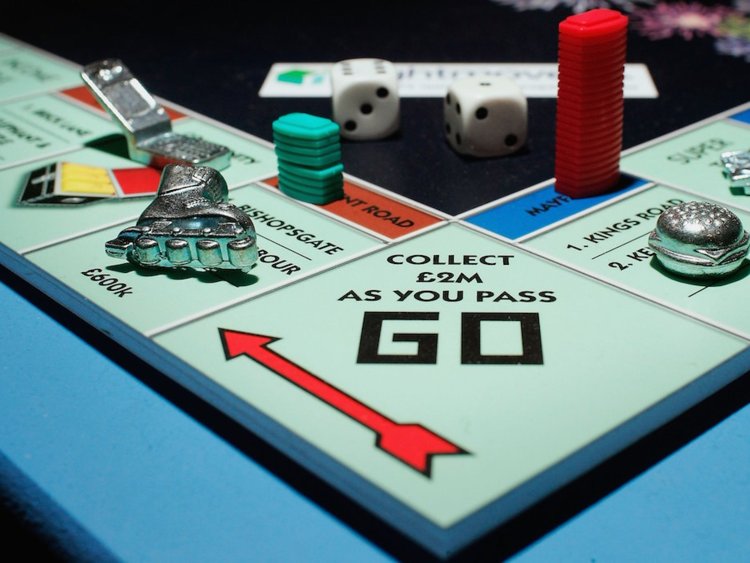

It involves a rather unpopular word, a word that one rarely drops into polite marketing conversations. Monopoly.

The argument goes like this. All businesses secretly crave monopolies. Since in a monopoly no one else can supply the market with what you make, you have control over every aspect of the value chain, the product, the experience, the service and critically the price. Freed from pesky competitive pressures, it’s a commercial nirvana.

The problem is that, aside from some notable exceptions like Google and Facebook that operate actual monopolies, most businesses will never enjoy any of the benefits of this rarefied commercial environment.

And according to my planning sage, that is how brands work. They mimic monopolies where real ones don’t exist. While any number of business can supply consumers with the products and services that you create, no other business can supply consumers with your brand. You have an actual monopoly over your brand which is immensely powerful if anyone gives a damn.

Make your brand sufficiently desirable and dominant in the minds of your customers (like perhaps those clever people in Cupertino) and you will start to experience the commercial benefits of this monopoly. From greater freedom over pricing and increased barriers to entry to greater resilience against reputational damage. In fact, the full gamut of benefits we accord to brands.

Indeed, whether you experience the monopoly benefits of your brand is quite a good test of whether you actually own any brands or merely a set of products with names.

Of course, you are mimicking a monopoly so there are limitations. Unlike in a real monopoly a great brand will rarely be able to defeat poor physical availability, it will not protect you in the long term from a substandard product and there will be limitations to the price the market will bear for your products and services.

But the idea that brands create financial value for organisations by building monopolies of the mind that mimic real monopoly conditions is a simple and elegant explanation that perhaps even the boys from South Park might understand.

First, we build brands. Second those brands mimic monopolies. Third, the result of these conditions creates profit.

And having just paid way over the odds for some boxers from Hamilton and Hare, pleasingly the concept seems to work for underpants too.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.