The power of powerful creative vehicles

Recently I have got really interested in the concept of creative vehicles.

Indeed I wrote about them for Campaign magazine in a piece about how much I hate the word ‘branding’.

By creative vehicle I think I mean a repeatable approach to communications that builds fame for a brand. The thing that your brand is famous for when it comes to advertising.

Their importance and power being the way that they drive attribution, at best making it inconceivable that your advertising could be for anyone but you. For instance, Kevin Bacon drives attribution for EE advertising as close to 100% as I have ever seen in my career.

To be clear creative vehicles are different to distinctive brand assets and I think more interesting. This is partly because distinctive brand assets are routinely treated as separate elements and while useful the concept is leading people to believe strongly attributed advertising is simply a matter of scattering a sufficient number of distinctive brand assets across the work. Creating and using one simple creative vehicle, which is of course one of the brand’s assets, seems to me far more effective.

Creative vehicles are also probably different to creative ideas. Ideas are conceptual constructs whereas vehicles are the tangible means by which ideas are carried and which bonds one idea to another beyond the lifetime of a campaign. For instance, campaigns for Compare the Market may come and go over time but the vehicle used to carry them is always Aleksandr Orlov and his famliy, native brand characters.

So perhaps we can agree that creative vehicles are powerful but how do you get one? In my experience, it’s hard to brief for a vehicle. To simply ask for a new repeatable character, format or world isn’t that rewarding perhaps because it’s not really the way that creative teams work. They tend to think in conceptual ideas not advertising real estate.

But it’s not very hard to work through the ideas you have and see whether you can develop a creative vehicle from them, i.e. what you can turn into a repeatable approach. Indeed, as ideas are developed and work on, you can start being more forceful about the need for a vehicle simply by asking what we are going to be famous for. And to be honest I find the argument that we are going to be famous for the idea alone, a little unsatisfactory.

This is not to say that all advertising has to have a creative vehicle that you can establish and work with over long periods of time. Some advertising doesn’t work like this, it’s more like a one-off brand experience that doesn’t establish a model for subsequent work but burns brightly in that moment. Perhaps Sony Bravia ‘Balls’ was one such example or Blackcurrant Tango (interestingly the original Orange Tango work used a repeatable format as its vehicle) And that is fine. But to be clear that work has to be utterly exceptional, Cadbury’s Gorilla exceptional.

It is also the case the some very successful advertisers have very loose creative vehicles. It’s hard to see a format or a story, less a brand character, in any Nike advertising. In this case the work is almost always a one-off idea but bonded to everything that has come before by a personality and tonality, by a ‘world’. And it’s this ‘world’ that the brand is famous for. But beware of this approach. The brands that make this work are few and far between and tend to have a commitment and discipline to their work that is hard to simply switch on. I remember Russell Davies used to tell people that asked him how to create advertising that is as good as Nike’s that they needed to “stop pretesting and wait twenty years”. Any advertiser can stop pretesting but few have the patience, diligence and discipline to forge those brand world’s.

When a team tells you that the thing that will bond their work to past and future advertising for the brand, is nothing more than the quality of the idea and the nature of the execution they better be working on the next John Lewis Christmas ad. This approach is phenomenally difficult.

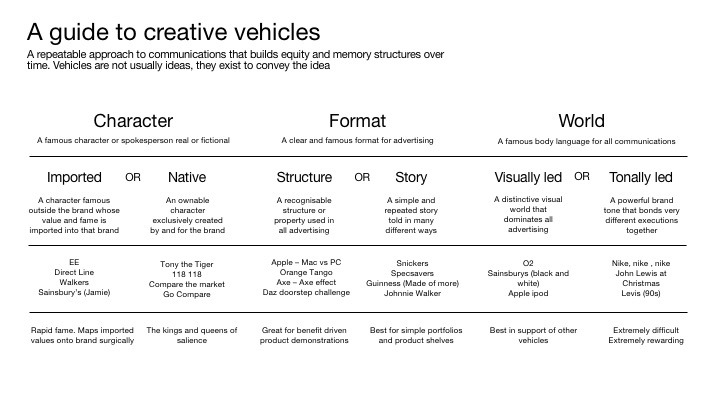

To help understand the nature of your creative vehicle I| have created a simple ready reckoner. This is very much work in progress, to be developed and built upon but it may prove useful.

And here is the original Campaign article:

Frankly, any metaphor that alludes to searing hide as a red-hot iron is driven into an animal’s flesh doesn’t seem like an entirely good look for contemporary marketing.

That’s why I hate it when people refer to ‘branding’.

The nether reaches of social media are awash with charlatans banging on about ‘branding’, how to improve your ‘branding’, ‘ten ways to better branding’ and the like. And calling themselves ‘branding experts’ or ‘branding agencies’. It’s the word ‘branding’, it’s horrible.

I admit, it’s a small thing and frankly there are bigger issues to be worrying about than a clumsy use of language. But like that ghastly habit people have of saying ‘creatives’ meaning more than one creative asset, using the phrase ‘branding’ is a poker tell that suggests someone doesn’t actually understand what they, or we do.

More seriously, it speaks to a fundamental misunderstanding, that brand building is about creating and using physical artefacts and symbols as if these ‘are’ the brand. When anyone with a passing familiarity with creating and nurturing great brands know that a brand is nothing more than a mental construct, existing only in the minds of real people.

Professional marketers are in the business of building brands not ‘branding’ anything. Least of all ads.

Ah yes, ad ‘branding’, the bête noir of planners and creatives everywhere. Without question, advertising needs to be attributed to the brand paying for it rather than to the competition. And it’s essential that new associations created by an ad are mapped onto a consumer’s understanding of the brand, so you need a means by which people can recognise which brand it is. But I have always found conversations about the level of ‘branding’ in an ad utterly sterile, deeply amateur and largely reduced to arguments about how long the logo is shown. Incidentally there is an absolute corker at the moment in which the Vodafone tadpole never leaves our screens.

That’s why the newly fashionable idea of distinctive brand assets is genuinely helpful. By exploring all the brand furniture that is genuinely associated with a brand, we have evolved a much better approach to ensuring that advertising benefits and benefits from, people’s understanding of that brand. And as a planner I get jolly excited by studies used to quantify the power of different brand assets, according to their fame and uniqueness. This is all a genuine step forward in the never-having-a-debate-about-the-length-a-logo-appears-ever-again-so-help-me-god department.

But I fear that all this distinctive brand asset stuff is inevitably being treated in a rather ham-fisted way. There appears to be a belief that simply dumping a whole load of distinctive brand assets into a piece of communication will do the job of attribution.

This stems from seeing distinctive brand assets as separate entities working alone rather than members of a system or structure, where each is only as good and powerful as the other elements of that system. The truth is that liberally sprinkling ads with assets is kind of like putting flour, butter, sugar and eggs in bowl and hoping they make an actual cake. The truth is we need to understand the power of the whole not just the parts.

A more helpful concept is the creative vehicle itself. A creative vehicle is a replicable approach to communications that consumers learn and indelibly aligns ad spend to effect. It is a consistently used creative vehicle not a simply a bunch of distinctive brand assets that really drives up brand attribution and drives down the money an advertiser needs to spend. In my day job, the staggering power of a well-known creative vehicle is demonstrated by the effect and efficiency EE derives from Kevin Bacon and Direct Line derives from Mr Winston Wolfe.

Obviously, characters and spokespeople whether native to the brand (like Aleksandr Orlov) or drawn from popular culture (like the Wolf himself) are not the only powerful creative vehicles though they have worked and continue to work stupendously well. A creative vehicle may also take the form of an ownable advertising structure (like ‘Keep Walking’ or ‘Food love Stories’), a story repeated in many ways (like the legendary ‘Should have gone to Specsavers’), an explicit visual world (Like Sainsbury’s most recent work) or an implicit brand world (anything from Nike in the last two decades and every John Lewis’ Christmas campaign).

Of course, most powerful vehicles employ more than one approach. I was reminded of this during the ‘the World Cup of ads’ run by BBH Labs last year, that was so conclusively won by Guinness Surfer. This extraordinary piece of film, is as powerful today as when it was created 20 years ago. But it was no one off, it employed a well-established creative vehicle involving a repeated story (the virtues of patience), and an incredibly distinctive visual world. Sure, many of the elements of this work might be dubbed distinctive brand assets but their power is in the vehicle that they are part of not as stand-alone agents of attribution.

If building brands is really your game, move beyond obsessing about your distinctive brand assets and identify the creative vehicle you are creating, buying or using – the communications approach that can be repeated over time, creating fame and fortune for your brand.

And leave ‘branding’ to the cowboys, in both sense of the word.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you so much for this article. Do you know any resources or authors to read about the creative vehicle concept?