What’s in a name?

It is not clear why, of all the things that might concern a business as we enter a year of economic and consumer uncertainty, changing your brand name would be number one on the list of priorities.

It is even less clear why you would want to spend a considerable amount of your cash telling the entire British nation about it, the vast majority of whom have less concern about your little endeavour than they have about the political situation in Azerbaijan. And still less why you would attempt to dress this spot of administrative deckchair rearranging as a benefit to any one except those hoping to win some cost savings from the corporate signage budget.

Nevertheless, none of this appears to have been of concern to the good people at the insurance company formerly known as Norwich Union. Their name change campaign is now coming to an end, not only having informed us of their act of brand vandalism but also having insisted that Norwich Union was a lacklustre name and that now they are called Aviva they will be far more successful. Just like the handful of celebrities desperate enough to mouth such arrant nonsense as “sometimes a name change isn’t just a name change, sometimes its a chance to show the world what you have always wanted to be”.

And so with the stroke of their pens Aviva has consigned a 310 year old brand to the corporate scrapheap. All the history, all the associations, all the good will, all the familiarity and three centuries of marketing investment. Gone.

Perhaps no one cares, though I might if I was a shareholder. You see these brand things we work with are desperately fragile, you mess with them at your peril. They can be the source of enormous commercial advantage or simply a silly name and a pretty logo. Was it really such a smart idea to change the name of Virgin Megastores to Zaavi? A deeply challenged business had the last vestige of brand advantage clinically and cynically snatched away, hastening the chilly embrace of the administrator.

Now I’m not suggesting that brand familiarity and affection alone will cut the mustard in these interesting times. A brand has to have a clear and clearly articulated role in peoples lives, you don’t need to look further than Woolworth’s sordid ending to understand that. In fact, the businesses that are disappearing first and fastest tend to brands that lack a point and offer goods and services that are available more conveniently and cheaply elsewhere.

And I’m not suggesting that a new entrant to the brandscape, whether through birth or a change of name, can’t be very successful very quickly either. The last decade has witnesses the arrival of gargantuan brands both on and offline, from Google (that WPP rates as the world’s most valuable) to Dyson.

But the issue is to create a real role in people’s lives and to do so with a fresh brand requires one fundamental and terribly unfashionable ingredient, clear product superiority. And this is what digital businesses have always instinctively understood and understood far better than the offline brands. Whether it’s an instantaneous way to purchase music, an encyclopedic inventory of books or an easy way to share video product performance has always been paramount for online brands or brands seeking to engage people online.

Advertising of any kind will need to learn that its role going forward will be to help create and dramatise these differences and not simply attempt to build brands through ludicrously expensive awareness campaigns, particularly those that are name changing not game changing.

So good luck to Aviva. Perhaps the loss of familiarity and affection won’t matter, perhaps the new name will be an overnight success and perhaps they have concocted a radically new approach to the business of insurance that will propel them into the brand stratosphere. Perhaps. My money is on this being a monumental act of corporate vanity and that it will take years and millions and millions of pounds for the business to recover.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I agree – although I think the Zavvi thing was engineered to protect the Virgin brand.

My guess is that they knew VM was faltering. Cue a buyout, rebrand and call to the administrators.

I’m extremely glad you brought this up Richard. To someone outside the industry this kind of crass idiocy is astounding and I’m interested to see what you lot make of this.

I was surprised you did not mention the Consignia fiasco from some years ago – an appalling disregard for the value of the Post Office brand and the humiliating (and remarkably swift) retreat by the management once their vandalism was revealed.

Do these people not learn?

Perhaps it is the same mentality that 50 years or so ago persuaded many apparently intelligent people to believe that their steel and concrete slabs would be preferable to the historic buildings they replaced. To me the abandoning of “Norwich Union” is in the same vein as the destruction of the Euston Arch.

Out of interest, as a forty year old, I was only aware of the loss of Virgin Megastore and until this article had no idea of who or what Zaavi was.

Thanks for bringing this up, you have got me riled.

PS. “Skate formal” – really?

Couldn’t agree more… complete waste of time and money and the destruction of a decent brand

I’d agree that these things are often ill advised, but I’d be inclined to give Aviva the benefit of the doubt – there are precedents of successful name changes too. Midland Bank was a household name with at least some valuable equity (people still remember it as the listening bank) and then embarked on an expensive overnight name change. Midland had existed for over 150 years in one form or another, and then was replaced with an acronym.

An acronym that is now Interbrand’s 27th most valuable brand in the world. As HSBC, the bank could shed its parochial roots and build a brand that stands for multiculturalism, open-mindedness and new ideas.

Aviva might well have jettisoned something valuable, but I wonder what it will allow them to build instead? And if they can tap into our current hunger for fresh starts, all the better.

Great article, and firmly agree. The point about clear product superiority is spot on – and exactly why the Norwich Union/Aviva thing will end up being little more than a good example of how to spend a load of dosh on a brand. And achieve the square root of bugger all.

But Dan did HSBC spend millions just announcing (rather than justifying) a name change?

To be honest I can’t remember

From memory I think they just announced it to begin with – they didn’t start talking about the benefits of being the world’s local bank for a couple of years. In fact, I think the ad was almost purely about name recognition (it repeatedly spelled H-S-B-C). It didn’t do much for the brand at all, but it paved the way for the new positioning.

Probably not the most efficient way to do things…

I don’t know, I think Norwich Union sounds a bit old and tired. Aviva sounds fresher and younger. Not sure if I think that is a good or a bad thing, but I thought starting fresh (or being perceived to do so) in a recession was a good thing. I think the long term benefits with the change in name are much bigger with this new name, and with TV spots being almost as cheap in the late 90s, why not do it now? Yes there is the argument that consumers are turning to old trusted brands, but aren’t they mostly the ones that are failing?

sorry, tv spots priced at late 80s prices

“It is even less clear why you would want to spend a considerable amount of your cash telling the entire British nation about it”

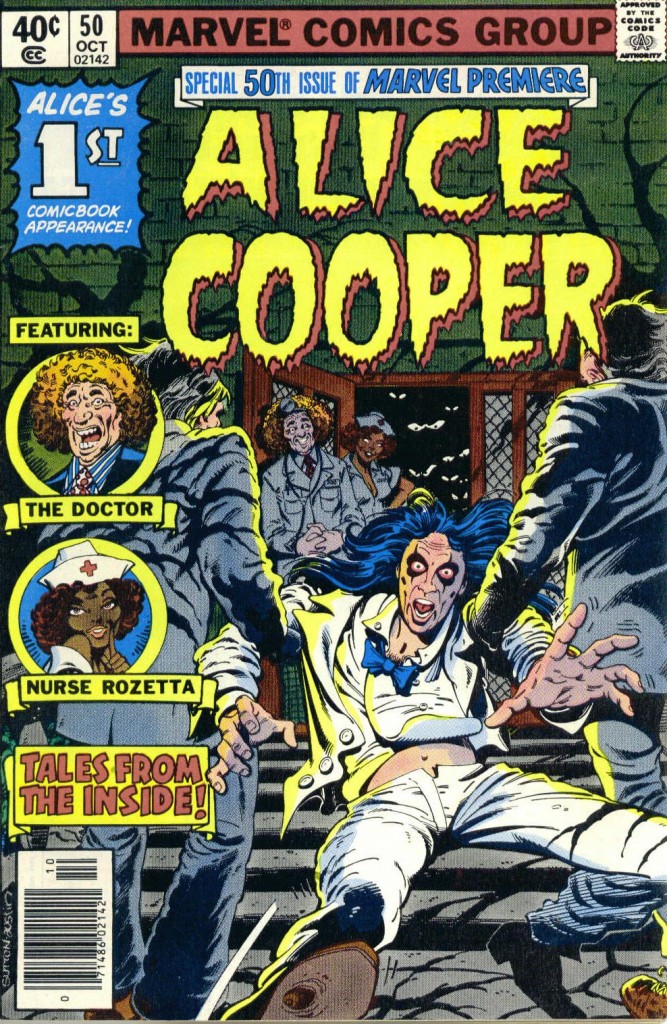

… especially when you made 1800 people redundant six months earlier. But I guess they had to find the millions to pay Ringo, Bruce, Alice and Elle from somewhere…

Not all name changes have been abject failure. Starburst and snickers, formally Opal Fruits and Marathon for those too young to remember the previous names, suffered little or not at all from their name changes.

Aviva is simply global brand positioning making ads cheaper to run in multiple regions without having to change the brand details. For the management it will simply be a cost Vs benefit exercise which at some point they have figured will pay back.

Although this campaign has relatively recently launched in the UK it’s been running in other markets for considerably longer and therefore the decision would have been made well before the current financial situation.

Will they loose brand equity and customers? Possibly. Will this be offset by the reduced costs? Maybe. Considering consumers in this space are price driven and therefore lees brand loyal will they still attract customers? If the price is right, definitely.

What goodwill, exactly? Among the families of people who pay life insurance premiums for years, only for NU to try to wriggle out of it when the finally pop their clogs, and even invoke the Insurance Ombudsman on their side, I’m sure there’s little but disgust for the name, the company and the people that work there. They can call it what they like.