3. Orthodoxy

“Orthodoxy, of whatever colour, seems to demand a lifeless, imitative style”

George Orwell, Politics and the English Language

George Orwell has much to teach the brand strategist.

At a very basic level he was a very accomplished writer who believed in total simplicity and economy in the way that he wrote and advocated that others do so too. He hated convoluted language and dead metaphors that have been shorn of their meaning.

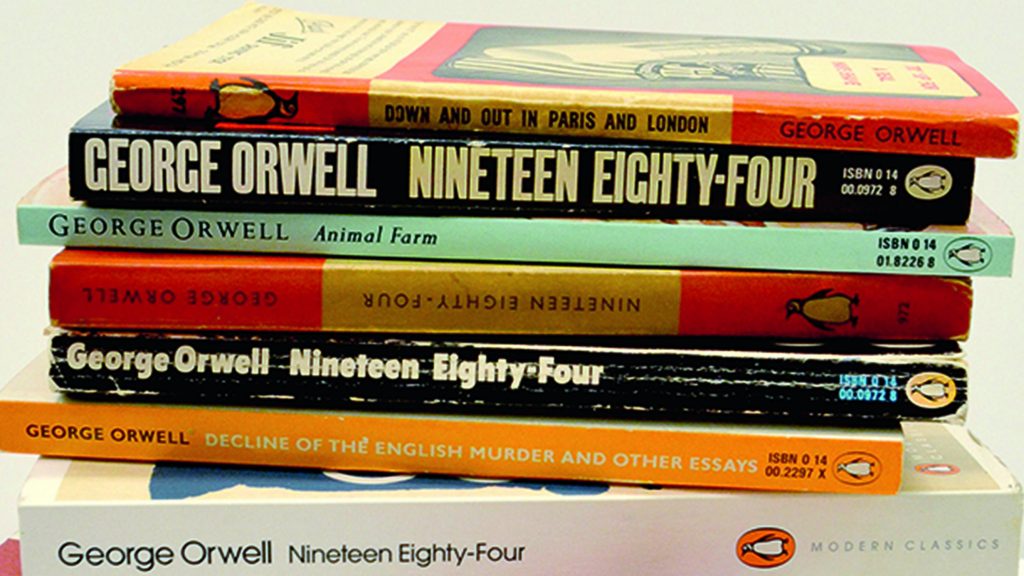

Anyone working with language, which is inescapable if you are creating brand ideas and writing brand strategy, should study Orwell. This is easier than you’d think since he taught himself to write in public. So his published work represents a writing journey and one that you can follow from the early ethnographic accounts like ‘Down and out in Paris and London’ and ‘The road to Wigan Pier’ to the sources of his enduring global reputation, Animal Farm and 1984.

In particular you must read his essay ‘Politics and the English language’. In my book much that you need to know about writing well is in that essay. As well as an all too contemporary explanation of the way politicians use language to deliberately obscure meaning.

But Orwell has so much more to offer you than writing lessons. Because if there was one thing that he hated the most in the world, second only to his abhorrence of totalitarianism, it was orthodoxy. And make no mistake he absolutely believed that the two were related.

By orthodoxy we mean anything that is an accepted wisdom, a best practice, an established way of doing things or a mainstream point of view. Greek in origin, the word orthodoxia means a righteous or correct opinion. It’s something that is not only fervently believed to be right and indeed righteous but also to an extent orthodoxy is policed by those who hold those beliefs.

In recent years we have seen how online orthodoxies are not only spread but also policed by echo chambers with a palpable sense of righteousness and religious zeal. Orthodoxies being distinct from facts, that may well be righteous and correct but are factual and not merely opinions.

You’d be well advised to steer clear of orthodoxies wherever you find them. For one thing they make for tedious conversations in which nothing new or interesting is ever said. While in the form of ‘best practice’ they act to stifle innovation and idiosyncrasy which is ironic given the place you most often find a discussion of best practice is in areas too new to actually have rules yet.

But orthodoxies are quite definitely no friend if you are trying to solve problems at their root cause and build brands that are distinctive and authentic – the eternal endeavour of the brand strategist. Orthodoxy will always thwart this ambition, offering stale but easily accepted ideas instead of solutions that challenge convention and get the job done.

As Orwell famously declared “Othodoxy is not thinking, not needing to think. Orthodoxy is death”. That isn’t merely a mild dislike of the echo chamber, he is likening peddling orthodoxy to death because there is no need for thinking. And of course, for Orwell the moment at which people ceased to think for themselves was the moment that they gave into darker forces.

This may seem rather dramatic and yet that is what is happening when you accept and project orthodoxy. You have ceased to think independently and critically. You take as read what other people think. And what other people think is your starting point for any endeavour, rather than casting off those accepted wisdoms and thinking for yourself.

So how do you defeat orthodoxy in your own work? Well one of the most helpful characteristics one can possess is inexperience. As the choreographer Twyla Tharp says “experience – the faith in ability and the memory that you have done this before – is what gets you through the door. But experience also closes the door. You tend to rely on that memory and stick with what has worked before. You don’t try anything new”.

I think that’s what’s meant in part when Dan Weiden implores us all to ‘walk in stupid’. Your nativity, inexperience and stupidity is one of your greatest assets. I could never undestand why agencies and clients always wanted people with automotive or financial services experience when what they desperately needed and need is blissful inexperience. What I call shaking the etch-a-sketch, if that reference isn’t so ancient to be completely useless to you.

Every category has its orthodoxies, the off the shelf belief systems that are never or rarely challenged. In your work you really do need to destroy them.

Telecommunications is about connection and connectivity, insurance is about protection, investments are for a rainy day, mortgages are for your dream home, energy is about your world. It’s not simply the content of a category’s communication that we are talking about, although any tour of the work from those categories will pretty quickly throw up the conventions. It is the fundamental beliefs of that sector and the people inside it that need to be challenged, because they stand in the way of getting to the truth and to being, doing and saying something different to the competition.

One of my favourite examples of rejecting orthodox opinion is found at the bottom of a gin bottle. If you had worked for a distillery business just a few years ago you would have encountered the vodka orthodoxy. At the time all of the interest and investment was going into vodka and not gin. Vodka was thought to be the white spirit of the future and gin was fervently believed to be stone cold dead. And then in 2009 three people with a brewing and distillery background decided to overturn this orthodoxy and launch the gin brand Sipsmith. Sipsmith not only became widely successful in its own right, selling to Beam Suntory in 2016 for £50m it established a new artisan gin category and gave the established players a shot in the arm. Gin is now growing far faster than vodka and just because three people challenged the righteous and correct opinion of the spirits business.

I’m afraid there is no short cut to being able to do this. You need to develop a visceral hatred for orthodoxies, to be able to smell them a mile off and turn against them. Orwell did’t just dislike orthodoxy remember, he said it was death. You must regard the best practice in any category as a form of death and decay.

You think you don’t do this, of course you do. But if you have ever, ever thought or said out loud the phrase ‘Gen Z’ or any other flat-packed marketing twaddle you have fallen prey, if only momentarily, to the forces of orthodoxy.

I have an almost physical reaction to the thing that everyone says or believes and a hunger for thoughts and ideas, for ways of seeing the world that I have never come across before. In my case its so extreme it’s almost an instinct and perhaps I can be over eager to rubbish the structures and belief systems of a category. |I mean there might be some merit in generational marketing for instance that rubbishing it denies.

But better to be wilful in your avoidance of orthodoxy than imprisoned in its clutches. You can always temper the extremes of your thinking and bring it back to an areas of greater consensus once you have found a new way of thinking about a brand or category.

And I really do approach a new project with wilful belligerence, with my orthodoxy senses tuned in, trying to hunt down what it is that everyone believes so that I can find the a fresher way to think about the brand or category.

When I started working on a private banking project I was determined that we would avoid the lazy thinking about affluent people that pervades this category. And the default strategy that private banking is about tailor-made financial solutions. This was the orthodoxy that pervaded private banking at the time and the category seemed unable to escape from its gravitational pull.

Of course at this level of banking the service is hyper personal and the solutions are bespoke but if you stay in that place you are going to have to split a lot of hairs to find anything distinctive to say about your particular offering.

The solution was to try something new. To have the sort of wealth that private banking serves you usually have to have done something quite extraordinary, to have developed an idea, a business or string of businesses that have created so much value that you have tens of millions in the bank. These people tend to be incredibly focused, incredibly driven and to know their world intimately. What they are often less aware of are the alternatives, other companies, other markets, other sectors, other approaches, other opportunities all of which might offer better returns and certainly improve the diversity of their assets than reinvesting in their own world.

In many ways the job of private banking is to show the super successful people the world outside their world. From the power of impact investing in sustainable businesses and sectors to creating philanthropic trusts with the other members of their family. This led to a brand idea in ‘illuminating the world outside their world’. It focused the entire offering on illumination of the unknown from conferences and events to sustainability programmes, content creation and communications. And not a bespoke tailoring metaphor in sight.

So recognise and reject orthodoxy whenever you see it and you will find that you have been set free. That beyond the thought police of your category there are infinite new worlds and places to play. Ways to think about the world that are untouched by your competitors and that are fresh and potentially very exciting to your customers.

And that is half the job done.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great advice. I am in your camp and have always struggled with clients citing “category” experience as a necessity to work on their business. Sharing a piece I wrote about it: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/stop-using-category-experience-criteria-hire-agency-nikhil-vaish?trk=portfolio_article-card_title

Nikhil recently posted…F**k Yeah, I’m Fifty.